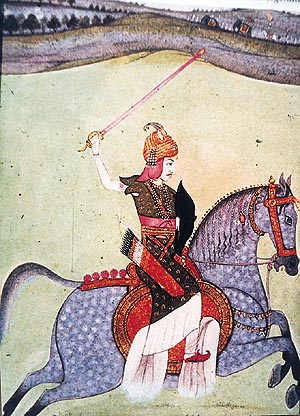

If we look at history before firearms came on the scene, we see much romanticism associated with swords and other blades. They were revered and even worshipped. The weapons themselves had stories and were often as well-known as the bearer. The swords that great men and women wielded, had legends of their own. The sword, now, however, is reduced to a ceremonial adornment, seldom drawn from the scabbard.

There’s more, however, to these swords than their legends. The oldest record of a sword-like weapon, or long-daggers, goes back to 3300 BC, in the Bronze Age. What we would consider a proper sword was not practical in the Bronze Age, due its tensile strength. Some innovations followed in China, but it wasn’t until the Iron Age that swords started getting their due, 12th century BC, onwards, when smiths discovered that by “adding carbon during smelting, they could improve produce an improved alloy”, which we now know as steel.

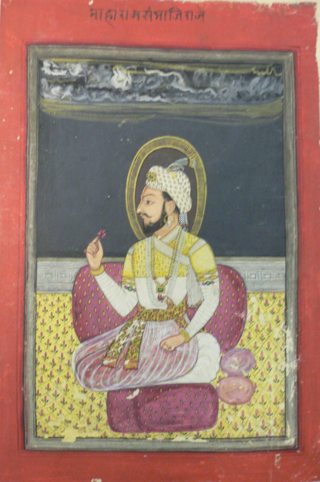

This painting is in the guest house of the largest R&D steel laboratory in the world, the Steel Authority of India, in Ranchi.

The first proper mention of steel, in India, comes around 326 BC when Alexander defeated Puru (often called Porus, in Western texts) at the Battle of the Hydaspes (modern-day River Jhelum). King Puru, though he lost the battle, did not lose his rival’s respect, and continued to rule his kingdom, Paurava. In-spite of the battle, there was mutual respect between these two kings. Puru offered to Alexander, as a token of respect, his sword, and a 100 talents of steel. If we assume that contemporary chroniclers used Greek standards, one talent is equal to 26kgs. That’s close to 3 tonnes of steel!

But why steel? Well, at those times, steel was rare, and therefore, more precious than gold. And this was not just any steel, these 100 talents were of Wootz Steel.

The word, Wootz, has its etymology in Urukku, or Ukku. Ukku is a Kannada word, but perhaps has its origins in classical Tamil, with “Ekku.” In the middle ages, in Russia, they were called the “Bulat” steels. In Persia they were known as “Pauhad Janherder”. Clear similarities, then, between these words and the common word for steel in India today: फ़ौलाद (Faulad).

According to Pliny The Elder, a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, we read of import of iron from the ‘Seres’ kingdom during the first century BC, which would refer to the Ancient Chera kingdom of South India. Another popular Roman travelogue, the Periplus of the Erythrean (Red) Sea, also mentions trade with the Chera kingdom, along the Malabar Coast of Kerala. Various accounts refer to Wootz as ferrum candidum (bright iron), ferrum indicum, sericum. Sericum, no doubt comes from Seres, or the Cheras. Yet, it became popular world over as Damascus Steel, perhaps because the finished product was seen in Damascus, Syria. While Wootz was cast in India, the fine swords made of this material were forged in Persia and Arabia, and probably seen (and sold) in Damascus. This is not to say that swordsmithery was absent in India. In the 12th century AD, the Arab traveller and cartographer Al Idrisi, wrote:

‘The Hindus excel in the manufacture of iron, and in the preparations of those ingredients along with which it is fused to obtain that kind of soft iron which is usually styled Indian steel (Hindiah). They also have workshops wherein are forged the most famous sabres in the world. …It is not possible to find anything to surpass the edge that you get from Indian steel (al-hadid al-Hindi)’

Elsewhere, Al-Biruni (973-1048 AD) says:

“There will never be another nation, which understood separate types of swords and their names, than the inhabitants of India…”

Arab accounts refer to Hindvi, Hindiah, or Hinduwani steel, which later got stylised to the European Ondanique, as well as Teling Steel, which undoubtedly refers to the Telengana region. This points us to the source; “…wootz ingots were produced in Southern and South Central India and Sri Lanka. The area of Hyberabad, formerly Golconda, was perhaps the most reputed area of the production of wootz.”

Damascus Steel – characterised by distinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water; CSMVS, Mumbai. Click to see larger version.

Due to the nature of Wootz and the forging method, swords made of Wootz are “characterised by distinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water.” Further, “Such blades were reputed to be tough, resistant to shattering and capable of being honed to a sharp, resilient edge.” [Link] The word, ‘Damas’ in Arabic language means water. Another reason, why, possibly, the swords got their name.

The romanticism of the sword, then, is no mystery. Before becoming a favourite sword, the material travelled many lands, passed through many hands. The steel, the forging, the beauty of the swords must have captured imaginations around the world. This wondrous alloy, of all things, has inspired poetry. The Russian poet, Alexander Pushkin immortalised ‘bulat‘ with a poem when he wrote in 1830:

All is mine, said gold;

All is mine said bulat;

All I can buy said gold,

All I will take, said bulat.

Wootz and swords made of Wootz continued to capture the imagination of the world. It was the subject of many stories, like the one between King Richard the Lion Hearted and Sultan Saladin the Saracen. This story, perhaps best explains what it meant to have a Wootz sword and what it is capable of.

The trade of Wootz continued in the 17th century, with accounts of Persia and Golconda trading this marvellous alloy, during the Qutb Shahi reign.

In recent history, Wootz finds mention again, during the Revolt of 1857. The swords had such a reputation that the British decided to destroy all Wootz swords. They had to build a special machine for this, because the shearing blades meant to cut the Wootz swords, themselves got cut by the tough Wootz blades.

*

India, today, is the 4th largest producer of steel, with 86.5 million metric tons of crude steel production. Given that this is the place where the finest steel was invented, there’s a long way to go. Sure, we don’t make swords anymore, but it is unimaginable to imagine a world without steel. Pretty much the same way, as it was, since the first Wootz sword was forged thousands of years ago.

*

I must make a special mention of the book, “India’s Legendary Wootz Steel—An Advanced Material of the Ancient World“, by Sharada Srinivasan and Srinivasa Ranganathan. This book has been the major source of reference for this post.

References

- Srinivasan, Sharada, and Srinivasa Ranganathan. India’s Legendary Wootz Steel: An Advanced Material of the Ancient World. Bangalore: National Institute of Advanced Studies and Indian Institute of Science, 2004. Print.

- Forbes, R. J. “The Early Story of Iron.” Studies in Ancient Technology. 2. Rev. ed. Leiden: Brill Academic Pub, 1964. 238-140. Print.

- Jeans, J. Stephen. “Early History.” Steel: Its History, Manufacture, Properties, and Uses. London: E. & F.N. Spon, 1880. 8. Print.

- Rickard, T. A. “The Primitive Smelting of Iron.” American Journal of Archaeology (1939): 100-01. Print.

- Sasisekaran, B., and B. Raghunatha Rao. “Iron in Ancient Tamil Nadu.” India; Metallurgy in India: A Retrospective. NML Jamshedpur. Web. 17 July 2015. .

- Sherby, O.D., and J. Wadsworth. “Ultrahigh Carbon Steels, Damascus Steels, and Superplasticity.” (1997). Web. 17 July 2015. .

- Sinopoli, Carla M. “Craft Products and Craft Producers.” The Political Economy of Craft Production: Crafting Empire in South India, C.1350–1650. Cambridge UP, 2003. 192-193. Print.